Introduction

A tape recorder translates audio signals through a tape head. When tape is played back the varying magnetic orientation retained by small magnets on the tape induces current flow inside the tape head. When amplified, the sound is similar to what was recorded.http://hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu/hbase/audio/tape.html#c3

Parts

- Tape casette player for tape head or MAGNETIC AUDIO TAPE RECORDER STEREO HEAD

- Metro cards, credit cards, casette tape

- Battery powered amplifier

Instructions

Video from http://www.nicolascollins.com/

- If removing the tape head from a player, remove the head with the cable attached to the player. You may need to extend the wires.

The back side of a stereo tape head has four connections. When wiring from a stereo head to a stereo plug, solder A to the tip of the plug, C to the ring and B and D and shield to the sleeve. When wiring a stereo head to a mono plug, solder A and C to tip and B and D and shield to sleeve.

If using a MAGNETIC AUDIO TAPE RECORDER STEREO HEAD solder the pins on the head to the sleeve and tip of the jack according to the diagram. And solder an additional connection between the shield and the metal shell of the head: -

If the head is connected to a working player. Turn on the device and rub the head over magnetic tape. If not disconnecting the head from the player, insert the plug into the amplifier and rub the head over some recorded media: metro card, credit card, casette tape (the emulsion side will be louder), etc.

To minimize the the hum, wrap the head in electrical tape. - Try attaching the head to a popsicle stick with electrical tape.

Image from artschoolshithead.wordpress.com

Video from Collins, Nicolas, Handmade Electronic Music

Prepared Tape Head

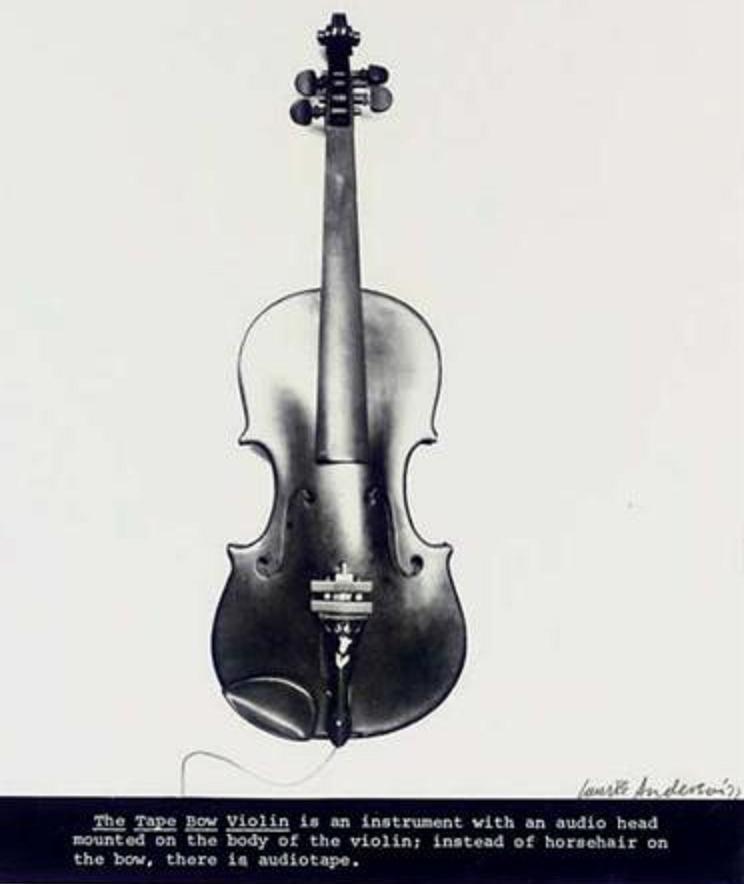

tape bow violin 2#

violin2demo

Metro Cards

The MetroCard is a magnetic strip debit card used in subway stations throughout the United States. The card is used by swiping it though a raised slot at designated turnstyles. Less than a second after the card is swiped, the remaining value on the card is displayed on a small screen and the person is permiited to walk through the turnstyle. Swiping the card too fast or too slow causes the machine to reject it.The MetroCard does not follow the ANSI BCD or ANSI Alpha magnetic strip formats used on credit cards and ATM cards.

From sidewalkscience

Magnetic stripes are made out of thousands of tiny particles of iron oxide, each about 20 millionths of an inch long. Because iron oxide is a magnetic material, all of these little particles are oriented in one of two directions-- you can think of them like arrows pointing north or south. When the card is blank, all of these little magnetic particles are oriented in the same direction, and by switching some of the particles around, the stripe becomes “encoded.” Just like binary code (0’s and 1’s) can be interpreted as characters and words and whole computer applications, the magnetic orientation of these particles can be read as information regarding your card’s serial number, balance, expiration, and so on.

On a MetroCard, tracks one and two hold information about the card type, expiration date, times used and remaining card value, while track three is encoded with a unique serial number. One inch of one of these tracks holds 210 bits of data, which translates to about 70 characters. Each time you swipe, your card is both read and rewritten to reflect your new balance.

Since the MTA completed its transition from token to MetroCard in 1997, the electronic fare cards have been used on many occasions to help solve criminal cases. In 2001, a transit worker named Christopher Stewart was accused of stabbing an ex-girlfriend to death in Staten Island. His alibi placed him on a ferry to Manhattan, but the trail left by his MetroCard told a different story—he’d swiped it on a bus near the scene of the murder twelve minutes after the crime took place. The new evidence won the case for the prosecution, and Stewart was convicted of second-degree murder.

MetroCards have been used to exonerate as well as condemn. In 1998, for example, a Brooklyn high-school student filed a federal civil rights case after being arrested for allegedly hopping a turnstile. The student had been on his way to the library to work on a school project, and ended up spending nineteen hours in custody instead. Two years after the incident, electronic records from the MTA showed that the kid had, in fact, swiped his card right before being picked up by the cops.

So, how is it possible to trace one MetroCard out of five million? The third track on a MetroCard is encoded with a unique serial number when the card is manufactured. When a MetroCard is swiped at a station or on a bus, the data on the card is both read and rewritten by a magnetic read/write head, and all data from the transaction is conveyed to the Automatic Fare Collection Database—a central computer database where all electronic transit histories are stored.

What does this mean for you, assuming you aren’t a public-transit-reliant criminal? If you buy your MetroCards in cash, your transit history trail can be traced only for as far back as the card in your wallet goes. If, on the other hand, you use a credit or debit card each time you purchase a new transit ticket, the Automatic Fare Collection Database knows who you are and where you’ve been going since you first stepped through a turnstile.

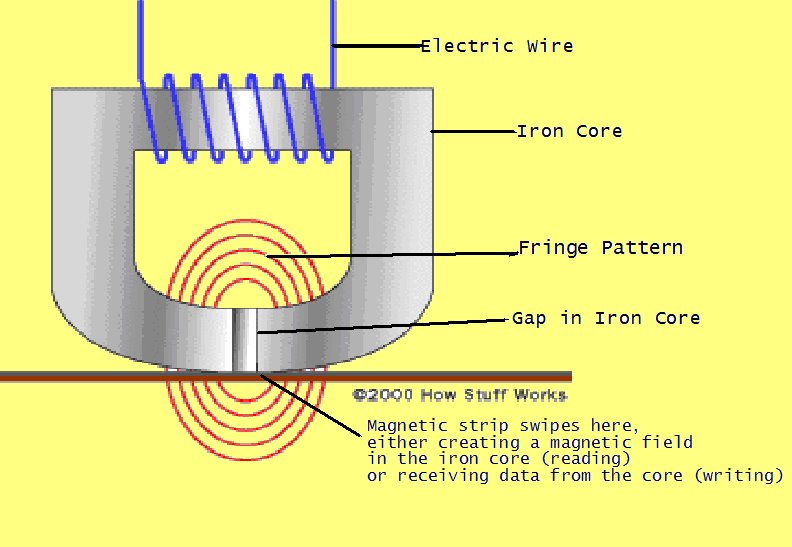

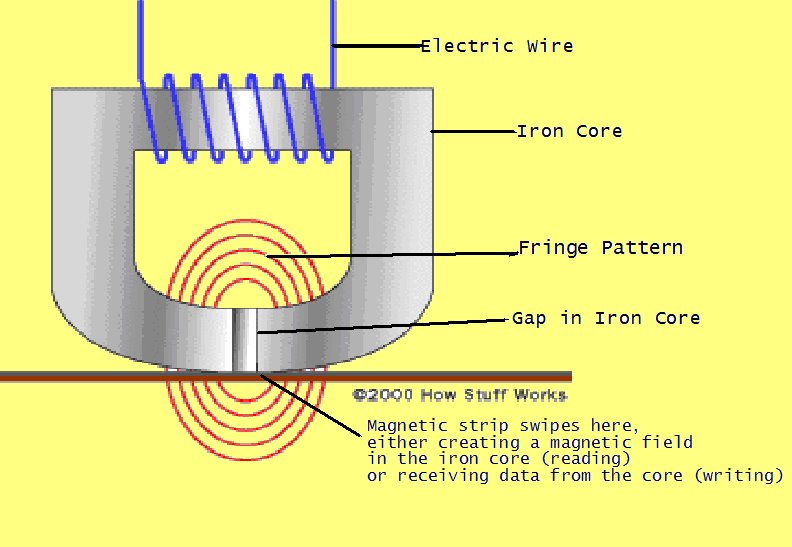

When you swipe a MetroCard, the data is read and rewritten by a series of magnetic “read heads” that perform different jobs. Magnetic read heads are these little pea-sized machines that convert the magnetic information on your card into electrical signals, and vice-versa. In fact, this technology works just like tape and video players, except that instead of the tape moving from spool to spool across the read head, your hand moves the magnetic stripe along as you swipe. This read head is a version of a simple electromagnet:

When you pass your card through the machine, an electrical pulse travels through the coiled wire and creates a magnetic field in the iron core. When the magnetic field reaches the gap in the core, a fringe pattern is created in order to bridge the gap. This fringe pattern interacts with the magnetic stripe on your card to write new information on it. The opposite process also occurs to read your card—the microscopic magnets on the stripe create a magnetic field in the iron core, which travels to the wire and sends electrical signals back through the wire.

On a MetroCard, tracks one and two hold information about the card type, expiration date, times used and remaining card value, while track three is encoded with a unique serial number. One inch of one of these tracks holds 210 bits of data, which translates to about 70 characters. Each time you swipe, your card is both read and rewritten to reflect your new balance.

Since the MTA completed its transition from token to MetroCard in 1997, the electronic fare cards have been used on many occasions to help solve criminal cases. In 2001, a transit worker named Christopher Stewart was accused of stabbing an ex-girlfriend to death in Staten Island. His alibi placed him on a ferry to Manhattan, but the trail left by his MetroCard told a different story—he’d swiped it on a bus near the scene of the murder twelve minutes after the crime took place. The new evidence won the case for the prosecution, and Stewart was convicted of second-degree murder.

MetroCards have been used to exonerate as well as condemn. In 1998, for example, a Brooklyn high-school student filed a federal civil rights case after being arrested for allegedly hopping a turnstile. The student had been on his way to the library to work on a school project, and ended up spending nineteen hours in custody instead. Two years after the incident, electronic records from the MTA showed that the kid had, in fact, swiped his card right before being picked up by the cops.

So, how is it possible to trace one MetroCard out of five million? The third track on a MetroCard is encoded with a unique serial number when the card is manufactured. When a MetroCard is swiped at a station or on a bus, the data on the card is both read and rewritten by a magnetic read/write head, and all data from the transaction is conveyed to the Automatic Fare Collection Database—a central computer database where all electronic transit histories are stored.

What does this mean for you, assuming you aren’t a public-transit-reliant criminal? If you buy your MetroCards in cash, your transit history trail can be traced only for as far back as the card in your wallet goes. If, on the other hand, you use a credit or debit card each time you purchase a new transit ticket, the Automatic Fare Collection Database knows who you are and where you’ve been going since you first stepped through a turnstile.

When you swipe a MetroCard, the data is read and rewritten by a series of magnetic “read heads” that perform different jobs. Magnetic read heads are these little pea-sized machines that convert the magnetic information on your card into electrical signals, and vice-versa. In fact, this technology works just like tape and video players, except that instead of the tape moving from spool to spool across the read head, your hand moves the magnetic stripe along as you swipe. This read head is a version of a simple electromagnet:

When you pass your card through the machine, an electrical pulse travels through the coiled wire and creates a magnetic field in the iron core. When the magnetic field reaches the gap in the core, a fringe pattern is created in order to bridge the gap. This fringe pattern interacts with the magnetic stripe on your card to write new information on it. The opposite process also occurs to read your card—the microscopic magnets on the stripe create a magnetic field in the iron core, which travels to the wire and sends electrical signals back through the wire.

From http://www.poormojo.org/pmjadaily/archives/001787.php

A couple of small media sources have noted recently that the New York City MTA has been experiencing increasing trouble from what they refer to as "the metro card system exploit" in the subway system. According to the MTA, this exploit has been around for years, but there is nothing they can do to correct it. Apparently the exploit is a result of the system being unable to read bent or damaged cards. To compensate for that error there is a built in fail safe that if a card is swiped 3 times and the computer reads a certain code that tells them it was damaged, on the 4th swipe it lets the swiper through. I guess they figure if someone is using a empty card they they wouldn't swipe it 4 times. Guess again! Here are the specifics:

- Bend the bottom right corner of your metro card up to the f (f part of the word facing). It is a 45 degree angle. Close the bend hard

- Swipe it 3 times and it says "please swipe again"

- On the 3rd time it says "please swipe again at this turnstile"

- Swipe one more time with the bend open and it says balance= $0.00, previous balance $2.00. GO

- Go.

"In 2005, the MTA changed the read-head technology and drove the card-bending trick into extinction. The change involved making the technology more sensitive, thus promoting MetroCard swiping to a low-level art form involving, if not beauty, a delicate combination of grace and speed."